Water Law

Overview and Introduction to Water Law[edit | edit source]

The Study of Water Law. Three central questions arise in the study of water law: (1) how do the established legal systems for allocating rights to use water compare; (2) how well do these systems perform in equitably allocating this precious resource; and (3) what are appropriate solutions to the unresolved issues in water law.

Legal Systems for Surface Water Allocation. American jurisdictions can be grouped roughly into three legal systems governing surface water uses: riparian; prior appropriation; and hybrid states.

Riparian Rights[edit | edit source]

Early History. Theoretically, early American decisions subscribed to a “natural flow” rule that gave every riparian owner the right to have water flow past the land undiminished in quantity or quality. The courts tempered the doctrine with “reasonable use” principles. Besides making exceptions for domestic uses, the early courts showed concern for existing users.

Modern Application. Today, all riparian doctrine states permit riparians to use water in a way that is “reasonable” relative to all other users. If there is insufficient water to satisfy the reasonable needs of all riparians, all must reduce usage of water in proportion to their rights. Because riparian rights inhere in land ownership, they need not be exercised to be kept alive. Thus, a landowner may initiate new uses at any time and other users must adjust their uses accordingly.

Modifications to the Law. Riparian rules have been altered extensively by statute and case law so that no modern riparian state is governed simply by common law. Typically, riparians must obtain permits from a state agency in order to use water. In some states, permits may also be available to non-riparians. Riparian landowners in all states have special rights to make use of the surface of waters adjoining their property.

Prior Appropriation[edit | edit source]

Early History. Two factors distinguish the legal system governing the use of surface water in the West. (1) the West was settled on lands owned by the federal government; private and state ownership of land arose after many uses of water had commenced. (2) Water is much more scarce throughout the arid lands west of the one-hundredth meridian.

Modern Application. Rights belong to anyone who puts water to a “beneficial use” anywhere (on riparian or non-riparian land), with superiority over anyone who later begins using water. Unlike riparian law, the development of water rights depends on usage and not on land ownership. Once a person puts water to a beneficial use and complies with any statutory requirements, a water right is perfected and remains valid so long as it continues to be used.

Hybrid Systems[edit | edit source]

Overview. California is the leading hybrid state, but Oklahoma, Texas, and several others maintain aspects of both prior appropriation and riparianism. Hawaii’s system is a unique combination of rights established under laws of the ancient Hawaiian Kingdom and recent statutes. Louisiana’s water law is unique as well, as it is adapted from the French Civil Code.

Special Types of Water[edit | edit source]

Overview. Most surface water is subject to riparian use, prior appropriation, or a mix of the two. Some types of water are different.

Groundwater. Groundwater law grapples with two dominant concerns: depletion of essentially nonrenewable stores of underground water and conflicts among competing well-owners. Even when water beneath the surface of land was connected with a stream or lake, the law treated groundwater under a separate set of rules or no rules at all. More progressive legal approaches now integrate groundwater and surface water management.

Diffused Surface Water. Water that is on the surface of land because of rain, melting snow, or floods is called diffused surface water, and it is generally not subject to water allocation rules. Nearly all states allow diffused surface waters to be captured and used by a landowner without state regulation or limitation. Most states allow landowners to divert or channel floodwaters away from their land if it is reasonable under the circumstances.

Public Rights[edit | edit source]

Overview. Water is legally and historically a public resource. Although private property rights can be perfected in the use of water, it remains essentially public; private rights are always incomplete and subject to the public’s common needs.

Intergovernmental Problems[edit | edit source]

Overview. Although the creation and regulation of rights to use water are primarily state affairs, there are important spheres of federal ownership and control. As noted above, federal navigational projects may affect the way state water laws operate; state and private interests may also be impacted by other exercises of congressional power, ranging from water development projects to environmental laws.

Reserved Rights. The doctrine of federal reserved rights traces to early litigation over water for Indian reservations. The Supreme Court held that Indian tribes could not be deprived of sufficient water supplies to make the reservation a viable place to live and to farm. To hold otherwise would have defeated the purposes the government and the tribes had in mind in agreeing to move the Indians onto the reservation. The reserved rights doctrine recognized a right to sufficient water to fulfill the purposes of the reservation.

Federal Actions Affecting State Water Rights. The United States is involved in activities that sometimes affect, and because of federal supremacy, preempt state water law.

Interstate Problems. Tensions frequently exist among states that share access to rivers, lakes, and groundwater sources. Water is considered an article of commerce.

Water Institutions[edit | edit source]

Overview. Chapter Ten describes various types of organizations formed to develop and distribute water, ranging from public municipal water systems to private irrigation districts. These organizations come in many different forms and may be established under state or federal law. They are the operating entities that deliver most of the water in the country.

The Legal and Scientific Language of Water Resources[edit | edit source]

Overview. Some terms (such as "surface water") have conflicting meanings.

Surface water. Also called "state water" at times. Defined under § 11.021(a) of the Texas Water Code.

Diffused Surface Water. Rainwater, mostly. Lasts until it evaporates, is absorbed, or runs into lake or stream.

Headwaters. The beginning of a river. Also known as the source.

Watershed. An area that naturally causes surfaces water to collect in a particular river, stream, or ocean.

Base Flow. The amount of discharge of a body of water uninfluenced by rain or precipitation.

Underflow. The water in rivers found in the sand, soil and gravel below the bed of the watercourse.

Environmental Flows. Refers to both instream flows and freshwater inflows into bays and estuaries.

Instream Flows. At its most basic level, “instream flows” means the water in streams, rivers, and lakes.

Riparian Rights[edit | edit source]

Overview. Although water law is primarily statutes now, it evolved from common-law efforts. Riparian rights, as originally envisioned, tended to be so strict they were impracticable to enforce. As a result, courts would commonly temper them to serve the particular interests in the case at hand. Now, Riparian rights tend to mirror tort claims such as nuisance to determine outcomes.

History of Riparian Doctrine in America. Foundation comes from English common law, developed in America (particularly in the East). Riparian doctrine often favored wealthier people who actually owned land next to water.

History of the Riparian Doctrine[edit | edit source]

European Precedents. Two theories governed in early English courts.

Prior Use. You can’t use the water if it deprives a prior user of water. Bealey v. Shaw, 102 Eng. Rep. 1266 (Eng. 1805). Replaced by natural flow in the 1820s.

Natural Flow Doctrine. Each riparian owner is entitled to the enjoyment of the watercourse without interference from others.

Development in the Eastern United States[edit | edit source]

Reasonable Use. Riparian rights entail each person full use of the water without prejudice to other owners. When using water as a non-riparian (prescriptive use, basically), you are only entitled to the amount used during the prescription. Tyler v. Wilkinson, 24 F.Cas. 472 (C.C.R.I. 1827); Herminghaus v. Southern California Edison Co., 252 P. 607 (Cal. 1926).

Measuring Reasonable Use. Reasonable use is determined by the fact-intensive process of comparing the uses of all riparians. Mason v. Hoyle, 14 A. 786 (Conn. 1888).

What does reasonable use protect? Most commonly the water flowing past one’s land, but also water purity, fish, to access the waterway, and protection from erosion.

Contours of the Riparian Doctrine[edit | edit source]

Overview. Based on location and attached to the land.

Rights. The landowner does not own the water itself, but instead has numerous usufructuary rights (rights to use). These right can be limited by public use or regulation, and include the right to: (1) the flow of the stream; (2) make a reasonable use of the waterbody, provided reasonable uses of other riparian users are not injured; (3) access to the waterbody; (4) fish; (5) wharf out; (6) prevent erosion of the banks; (7) purity of the water; (8) claim title to the beds of non-navigable lakes and streams.

Duties. Riparian owners must not interfere with other Riparian users under the reasonable use doctrine.

The Basis for Riparian Rights—Riparian Land[edit | edit source]

Overview. In a pure riparian jurisdiction, only the owner of riparian land acquires rights to make use of the adjacent watercourse. This section defines what constitutes riparian land, the types of water bodies to which the owner of adjacent land may hold rights, and how subdividing riparian land impacts water rights.

Overview 2. The law distinguishes between riparian land and non-riparian land based on the somewhat artificial concept of ownership. Only the owner of a parcel of land touching a watercourse—contiguous with the water’s edge—has riparian rights. Restatement (Second) of Torts § 843. Riparian rights to use water attach only to riparian land contiguous to the watercourse, and do not extend to any portion of a parcel that is outside the immediate watershed of the watercourse.

Defining Riparian Land[edit | edit source]

Overview. To establish use of water rights, the owner must own the land "abutting" the natural watercourse.

Watercourse. The water must flow in a particular direction by a particular channel, having a bed with banks that discharges into something else. It can be dry sometimes, but must have a well-defined and substantial existence.

What is a watercourse? Depends on the jurisdiction. But some common examples are: (1) streams, (2) lakes and ponds, (3) springs and other natural water bodies, (4) underground watercourses. (5) oceans and bays, (6) out of basin waters, and (7) artificially created watercourses.

Water mark. Whether the riparian right extends may depend on ownership of the high or low water mark. It depends on the statute. Because of this, rights may be seasonal at times.

Grants to non-riparians are sometimes permitted. Some jurisdictions forbid any use outside the watershed, though many permit grants to use riparian water on non-riparian land, so long as the use is reasonable. Pyle v. Gilbert, 245 Ga. 403, 265 S.E.2d 584 (1980).

Doctrines to determine riparian rights. Two major doctrines: Source of Title and Unity of Title. Most states have a statutory modification that finds some middle ground between the two.

Source of Title. Water may be used only on land held as a single tract throughout its chain of title; once a non-riparian segment is severed, it forever loses its riparian character.

Unity of Title. Any tracts contiguous to the tract abutting the water are considered riparian so long as all of the tracts are held under single ownership, regardless of when acquired.

Measure of Riparian Rights—Reasonable Use[edit | edit source]

Overview. All riparian states follow some version of reasonable use.

Second Restatement of Torts. As found in §850A (1979). Factors that affect determination are:

a. Purpose of the use;

b. suitability of the used to the water course, or Lake;

c. The economic value of the use;

d. The social value of the use;

e. The extent and amount of the harm it causes;

f. The practicality of avoiding the harm by adjusting the use or method of use of one proprietor or the other;

g. The practicality of adjusting the quantity of water used by each proprietor.

h. The protection for existing values water uses, land, investments and enterprises, and newline the justice of requiring the user causing the harm to bear the loss.

Riparian Rights vs. Riparian Rights: Whose Use Wins?[edit | edit source]

Overview. All § are from Restatement (2nd) of Torts (1979).

Riparian v. Riparian (§855). Determine “reasonable use” (balancing of factors per §850A). If plaintiff or defendant makes a non-riparian use it’s just a factor; i.e., reasonableness is not “controlled” by non-riparian use (§855); usual balancing test.

Reasonableness of competing uses. Courts often apply §850A factors against competing uses. Harris v. Brooks, 283 S.W.2d 129 (Ark. 1955) (finding that when a farmer drew irrigation from a lake, the use became unreasonable once the lake was below “normal” levels, thus interfering with boating, a non-consumptive use).

Non-Riparian (P) v. Riparian (D) (§856). Riparian is only liable under three scenarios.

Scenario 1: Riparian Grant. Riparian use is unreasonable, causes harm to plaintiff, and plaintiff's use is under grant from riparian.

Scenario 2: Government Authority. Regardless of reasonability, if defendant harms plaintiff, and plaintiff's water right is based on governmental authority, permit, or license.

Scenario 3: Public Use. If riparian uses water in a way that interferes with public right (like access).

Riparian (P) v. Non-riparian (D) (§857). Basically the inverse of the above. Non-riparian is liable for any interference with Riparian’s use, unless non-riparian’s use is (1) reasonable and under grant from riparian, (2) under a gov't permit or license, or (3) exercise of a public right.

Limits on Riparian Rights[edit | edit source]

Unreasonable Use. If a new riparian use emerges, an existing right can be lost or diminished because it is deemed unreasonable with respect to the other riparian rights in the system.

Prohibition of Use on Non-Riparian Lands and Its Exceptions. Many pure riparian jurisdictions continue to hold that any non-riparian use that interferes in any way with a riparian use is per se unreasonable. Stratton v. Mount Hermon Boys’ School, 103 N.E. 87 (Mass. 1913).

Which test to apply: No-Harm or Reasonableness? The restatement ultimately adopted the stance that a reasonableness test is in order. Whether the use of water is on riparian or non-riparian land is not dispositive, like it is in the no-harm test.

Scope of Riparian Uses[edit | edit source]

Overview. Sometimes, owning the shore means owning the bed to, allowing them to fill it in or improve it. This often depends on whether the waterbody is navigable. Navigable waters are often burdened with an "easement" for public use.

Reciprocal Uses. Owning a slice of the lakebed entitles you to reasonable use of the whole lake. Beacham v. Lake Zurich Property Owners Ass’n, 526 N.E.2d 154 (Ill. 1988).

May only use in original watershed. Riparian rights attach only to an owner’s land within the watershed. Gordonsville, Town of v. Zinn, 106 S.E. 508 (Va. 1921). If you own a separate piece of non-riparian land, or land in another watershed, that doesn’t mean you can use the riparian water on those tracts freely. Stratton holds differently but is a minority rule.

Waterbodies developed to promote recreational use. Dredging a canal from a lake to subdivided parcels doesn’t grant the parcels riparian rights automatically. Thompson v. Enz, 379 Mich. 667, 154 N.W.2d 473 (1967).

Natural v. Artificial Lakes. Depends on the jurisdiction. Case law on 97 provides more detail (unnecessary to describe).

Can the Public Bootstrap? When artificial modifications make a non-navigable waterway navigable (navigable waters usually being open to public use), does the public gain access to it? The majority says no: public use doesn't attach to newly-navigable waters.

Transformation from Artificial to Natural. Sometimes, canals and ditches are eventually treated as natural if they're around long enough, or detrimental reliance is shown. Again, it depends on the jurisdiction.

Preference for Domestic Uses. Domestic needs of the riparian landowner are prioritized. Examples are drinking, washing, and watering small gardens or a few livestock. Most jurisdictions allow domestic use regardless of consequence to lower stream users.

Irrigation, Industrial, and Mining Uses. These are considered artificial uses, and pollution is a special issue when dealing with these issues.

Municipal Uses. Courts have split on the question of whether municipal water systems qualify as riparian users. The more prevalent, and historic, view is that a public water system is only a riparian user with regard to parcels it owns along the watercourse. Statues often broaden this power as necessary.

Storage Rights. Under the reasonable use rule, a riparian user can impound water so long as the reasonable uses of others are not impaired. This includes when the water is released.

Scenic Rights. Recently, courts have begun to hold that riparian rights include an unobstructed view of the river.

Loss of Riparian Rights[edit | edit source]

Overview. Generally, you can’t lose rights through non-use.

Changing Waterways. Through accretion and avulsion, a waterway's abutments often change, and with them riparian rights. Generally, property lines change with the slow, natural accretion. Avulsion is considered "act of God" events, and ownership does not shift with the river. You can lose rights overnight due to this (though it's very rare).

Permit Requirements. Vast majority of states now include statutory system to implement right. You can’t permanently lose the riparian right though—you just need to correct and reapply.

Eminent Domain. The Government can take your land for public purpose.

Transfers of Riparian Rights[edit | edit source]

Reallocation. When Riparian land is sold, it's assumed the riparian rights go with it. This assumption is rebuttable in court. Severance is generally discouraged, but it is permitted.

Prescription. Must show the typical elements of adverse possession (actual, open and notorious, hostile, exclusive, and continuous). Obtaining a prescriptive right turns on two factors: whether the person against whom the prescriptive right is sought is (1) a riparian or a non-riparian owner, and (2) upstream or downstream from the riparian plaintiff.

Upper Riparian use is generally not adverse. An upper riparian owner’s use is not adverse unless it unreasonably interferes with the rights of lower riparian owner. A lower riparian can assume his upper neighbor is only using as much as his right allows, unless the lower is put on actual notice, or the circumstances are such that the party is presumed to know. Pabst v. Finmand, 211 P. 11 (Cal. 1922).

Prescriptions do not run upstream. Downstream users cannot prescript use from an upstream user.

Non-Riparian Use. Any diversion by non-riparian is de facto open and notorious. A successive invasion for the statutory period can transform into a prescriptive right.

Prior Appropriation

Overview. Water rights are granted based on the time when a person applies a particular quantity of water to a beneficial use. Those rights continue so long as the beneficial use is maintained.

How do you obtain an appropriative right? (1) availability from un-appropriated waters or naturally occurring waters, (2) establish priority of rights, or (3) perfections of rights.

Perfection of rights. The elements are (1) intent to appropriate, (2) a diversion, and (3) beneficial use.

What do you get with an appropriative right? (1) Usufructuary ownership, but not water ownership; (2) priority amongst other prior appropriators. (3) ability to transfer, assign, and mortgage; (4) validity as long as it is used.

Elements of Appropriation[edit | edit source]

Elements of Prior Appropriation. The basic elements of a valid appropriation are: (1) Intent to apply water to a beneficial use; (2) an actual diversion of water from a natural source of surface water; (3) application of the water to a beneficial use within a reasonable time.

Intent[edit | edit source]

Overview. Can be a very simple act as long as it outwardly manifests desire to appropriate.

Relations Back Doctrine. Intent may be the “time stamp” of the diversion, instead of the actual diversion. Under this doctrine, appropriation is completed when either: (1) actual diversion for beneficial use, or (2) intent to divert is manifested, formal notice given, and work is commenced within the statutory scheme and prosecuted diligently. Sand Point Water & Light Co. v. Panhandle Dev. Co., 83 P. 347 (Idaho 1905).

Steps to triggering relation back. There are two prongs: intent prong (subjective) and overt acts prong (objective).

Subjective Prong. The simpler analysis: did the party intend to appropriate the water?

Objective Prong. (1) Manifest the intent, (2) demonstrate a substantial step toward application to a beneficial use (the first "open act"), and (3) action constitutes adequate notice to interested parties.

Diversion[edit | edit source]

Overview. Initially, only man-made were allowed. This has been relaxed somewhat.

Due Diligence Required. Once intent manifests, the party must proceed within a reasonable time frame. This is most often statutory.

Exceptions to the Diversion Requirement. Many states now hold diversion is not necessary unless it is required for the beneficial use. In re Adjudication of Existing Rights to the Use of All the Water, 55 P.3d 396, 402 (Mont. 2002). Many states have also recognized instream appropriations.

Beneficial Use[edit | edit source]

Overview. Drives the analysis of appropriative rights. It is the "basis, measure, and limit" of an appropriative right. It is based on changing societal values. Must be significant, not incidental.

Definition. As with most legal terms “it depends.” It depends on the state, and what statutes and courts think is a beneficial use at the time of decision.

Analysis. When determining what is a beneficial use, first look to the jurisdiction’s statutory scheme, then supporting case law. If it’s still uncertain, make an argument based on (1) the fact pattern or (2) personal views concerning the issue.

Waters Subject to Appropriation[edit | edit source]

Waters made available by human effort. Sometimes water ends up in a natural stream at times and places and in quantities other than that which would normally occur in nature. This may be because irrigation return flows delay the seasonal decline in natural streamflow, or it may be the result of massive diversions from one watershed to another.

General Rule. Water that would never be available in the stream except for human efforts can be used without restriction by the person responsible for its being there, and it is not subject to appropriation until that person abandons it.

Distinctions among types of water. Courts draw distinctions between foreign and developed water and salvage water.

Foreign and Developed Water. Water that would not be in the system but for human interventions (i.e. interbasin transfers). This water may generally be used, but not appropriated fully. That means the person importing the water into the basin can alter their activities with no legal restraint (i.e. stop importing, import less, etc.). City and County of Denver v. Fulton Irrigating Ditch Co., 506 P.2d 144 (Colo. 1972).

Salvage Water. Recovered from existing uses or losses withing the original watershed. It may be recaptured, and is subject to appropriation.

Priority and Preferences[edit | edit source]

Qualifications of the Senior’s Right. Seniors cannot waste water or change their use if it adversely affects a junior.

Futile Call Doctrine. If a senior would "call" water from a junior, but waste would cause the water to not make it, the junior can continue to use the water. Senior call can call if they would get "any beneficial use" out of the water, accounting for waste.

“Any” beneficial use. This strict enforcement can cause waste. State ex rel. Cary v. Cochran, 292 N.W. 239 (Neb. 1940) (finding that juniors must allow 700 cf/s pass them so that the seniors could get their 162 cf/s).

Extent of the Appropriative Right[edit | edit source]

Reasonably Efficient Means of Diversion. Typically, reasonableness is measured from when the equipment was built, not current-day standards. Sometimes, courts will say that highly inefficient systems are wasteful, and thus not a beneficial use. Washington Dept. of Ecology v. Grimes, 852 P.2d 1044 (Wash. 1993); Schodde v. Twin Falls Land & Water Co., 224 U.S. 107 (1912). Some progressive jurisdictions (like Idaho) require a senior to use reasonable efficiency before calling in a water right.

Public Trust Doctrine. Water is a public and common resource, and is not subject to full privatization. The reach of this doctrine varies wildly from state to state.

Public Trust as a limit on private appropriations. A state can declare maintaining water levels as in interest of the public, preventing others from taking water out. Mono Lake.

When can the public trust be extinguished? Only when extinguishment widens the scope of the trust, or such extinguishment does not substantially impair the public’s use.

Recapture and Reuse[edit | edit source]

Overview. Salvaged water generally can be recaptured and reused by an appropriator if: (1) the total used does not exceed rights under a permit or decree; and (2) the recapture and reuse occur within the land for which the appropriation was made.

Total Use Must Not Exceed Water Right. Consumption may be increased by reuse without regard to junior harm under two conditions: (1) it does not exceed the user’s “paper right,” and (2) there is no “change of use”—a change in the place, purpose, or time of use, or the means or point of diversion. Green v. Chaffee Ditch Co., 371 P.2d 775 (Colo. 1962).

Reuse Limited to Original Land. The general rule is that one may recapture and reuse seepage and “waste-water” so long as it is within the original land and for the original purpose of the right. Estate of Steed v. New Escalante Irrig. Co., 846 P.2d 1223 (Utah 1992).

Seepage. A person that appropriates runoff from another is junior to all other appropriators. The person creating the seepage may stop the runoff with no legal liability.

Procedures for Perfecting and Administering Rights[edit | edit source]

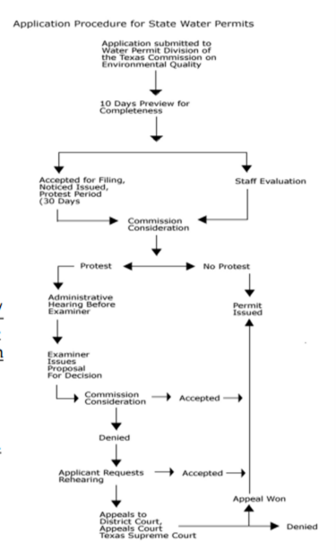

Permit Systems[edit | edit source]

Overview. The chief purpose of administrative procedures is to provide an orderly method for appropriating water and regulating established water rights.

Permits are Required for Appropriation. State law requires a permit as the exclusive means of making a valid appropriation. Wyoming Hereford Ranch v. Hammond Packing Co., 236 P. 764 (Wyo. 1925).

Statutory Criteria. In most states, this requires evidence of: (a) beneficial use;

(b) availability of unappropriated water at the time and period of use; (c)

no harm to prior appropriators; (d)

adequate diversion facilities; and

(e) possessory interest in the property where water is to be put to beneficial use.

Obstacles to Appropriation in the Permit System. On many streams, the “paper rights” to divert water far exceed the quantity of water actually flowing in the stream. This is a result of two phenomena: (a) many users may depend on the same water, as downstream users divert water that has already been diverted and returned by upstream users; and (b) the most junior rights may be exercisable only in years of heavy flow or low senior usage. Thus, many streams in the West are “over appropriated.”

Public Interest Considerations. Laws generally authorize the state to reject applicants that would violate the public trust. What this means can be hazy at times, though Alaska’s statute provides a good enumeration of factors, including: (1) benefit to applicant; (2) effect of resulting economic activity; (3) effect on fish and game and recreation; (4) public health effects; (5) loss of future alternative uses; (6) harm to others; (7) intent and ability of applicant; (8) effect on access to navigable or public waters.

Adjudication—How Water Rights are Decided[edit | edit source]

Overview. There are three general types of judicial procedures affecting water rights: general stream adjudications; appeals of agency permit decisions; and resolution of conflicts among individual appropriators.

General Stream Adjudications (GSAs). State-initiated adjudications proceed according to rules set by legislatures. They typically require all water rights claimants to state and prove their water rights relative to all other appropriators.

Review of Agency Permit Decisions. Once an official or agency makes a determination on an appropriation permit, it is final unless someone appeals. Appeals may go to another administrative level before proceeding to court. In some states, the court engages in a trial de novo, but most appeals are based on the administrative record, and administrative decisions will only be overturned if they are arbitrary and capricious or lack substantial evidence.

Conflicts Among Water Users. One or more water users can sue other water users who allegedly violate their water rights. The court’s decision generally binds only those who are parties. In some states, administrative bodies may have authority to resolve conflicts between individual water users. Decisions of an administrative body are subject to judicial review either on appeal or as a required step in the permitting process.

Transfers and Changes of Water Rights[edit | edit source]

Overview. Water rights in most states pass with the land upon its conveyance unless otherwise provided in the deed. When land is divided, a pro rata portion of water rights may accompany each parcel. Stephens v. Burton, 546 P.2d 240 (Utah 1976).

Water Rights may be transferred separately from land. Water rights may also be granted separately from the land, or by a reservation of the water right by the grantor upon conveyance of the land.

Transfers for different use are complicated. Transfers for uses in different locations, for different purposes, at different times, or involving changes in the points of diversion or return are more complicated, as the rights of other appropriators must be protected under the “no harm” rule.

Interbasin Transfers. The seminal case of Coffin v. Left Hand Ditch Co., 6 Colo. 443 (1882), involved a diversion of water out of the basin of its origin. The court recognized that the appropriation doctrine is fundamentally different from the doctrine of riparian rights in that it allows such diversions.

Changes in Use[edit | edit source]

Overview. Changes in the purpose of use only invoke the no harm rule when water is put to a different type of beneficial use.

What is Different Type? Generally irrigation to municipal, or power generation to irrigation. Not irrigation to more consumptive irrigation.

No Harm Rule. Whenever one seeks to change the point of diversion, or the place, purpose, or time of using a water right, special protections against harm to other appropriators apply.

Protections to Juniors. Seniors are obviously protected, but juniors are allowed to enjoy the conditions of the stream they had when they made the appropriation.

Not all harm is prevented. Reuse or more intensive consumptive use of the water on the same land for the same general purposes (e.g., irrigation), changes in use of imported water, and, in some jurisdictions, certain changes in the point of return are not covered.

A Change in Diversion is not an Increase in Diversion. The right is limited to the amount of water historically used even if that amount was less than the full amount of the decreed right. Orr v. Arapahoe Water and Sanitation District, 753 P.2d 1217 (Colo. 1988).

Loss of Appropriative Water Rights[edit | edit source]

Overview. Unlike riparian systems, you can lose water if you don’t use it.

Abandonment. Mere nonuse is not enough to claim abandonment. The person claiming abandonment must establish an intent to abandon. If you don’t use the water for an unreasonably long time, it can create a rebuttable presumption of intent to abandon, the length of time differing based on the jurisdiction. Haystack Ranch, LLC v. Fazzio, 997 P.2d 548, 553 (Colo. 2000).

Rebutting the presumption of abandonment. The owner must show facts or conditions justifying the nonuse, but it needs to be more than general unsupported reasons. Natural disasters, financial, economic, or legal obstacles are good reasons, though courts don’t like “waiting for a better business opportunity.”

Forfeiture. Unlike abandonment, you don’t have to prove intent to abandon. Simply not using the water for the statutory period merits forfeiture. The burden of proof rests on the person proving forfeit. This method depends heavily on the jurisdiction. Some statutes still allow forfeiture where evidence is inadequate to prove intent to abandon. Jenkins v. State, Dept. of Water Resources, 647 P.2d 1256 (Idaho 1982).

Adverse Possession and Prescriptive Rights. Generally speaking, this is rare and frowned upon in pure appropriative states. This is because water is a resource that is held in public trust and is difficult to measure. Some states have gone so far as to abolish prescriptive rights to water, others have struck a middle ground in allowing prescription against private parties.

Physical Access to Source and Transportation of Water[edit | edit source]

Overview. Keeping this basic because we didn’t talk about it in class.

Across Federal Public Lands. Basically passed a bunch of laws that said “people can move water across this land if they have to.”

Across Private Lands Under State Law. Generally doesn’t prevent perfection of the right, but requires the trespasser to indemnify the owner.

Appurtenancy of Ditch Rights to Water Rights. The right-of-way for a ditch and a water right are usually considered appurtenant to one another—conveyance of one carries the other with it unless reserved in the conveyance. Ruhnke v. Aubert, 113 P. 38 (Or. 1911).

Storage[edit | edit source]

Overview. Keeping this basic because we didn’t talk about it in class.

On-channel and off-channel storage. On-channel storage doesn’t take the water out of the stream, like a dam. Off-channel requires a diversion and transport to get the water to the storage facility.

Legal Differences between on- and off-channel storage rights. There are none.

Limits on Storage: the “One-Fill” Rule. A general rule (that can become complex in application) is that the appropriator cannot use their annual priority storage right to store a cumulative quantity greater than the reservoirs capacity. Basically, if your tank holds 100 af, you can’t drain and fill it over the year to store more than 100 af total.

Hybrid Systems and Other Variations[edit | edit source]

Development of Hybrid Systems[edit | edit source]

Overview. Ten states employ a mixture of riparian and appropriation doctrine in their water laws. They include the four West Coast states (California, Oregon, Washington, and Alaska) and the six states that straddle the 100th meridian—the dividing line between the arid West and the relatively wet East (Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, and North Dakota).

Hierarchy in a Hybrid System. As always, it depends on the jurisdiction; however, California has a sensible approach I’ll include for reference. Rights, from senior to junior, are: United States, appropriations before title to the land was claimed, title owner of the land, subsequent appropriations.

Modifications of Riparian Rights in Hybrid Systems[edit | edit source]

Overview. Riparian rights are difficult to reconcile because they require a continued flow, where prior appropriation can run a river dry.

Reasonable Use Limitations. Early enforcement of riparian rights were too strict. Now, a riparian cannot defeat an appropriation unless undue interference with the riparian’s reasonable use of the water is proved. Tulare Irr. Dist. v. Lindsay-Strathmore Irrigation Dist., 45 P.2d 972 (Cal. 1935).

Extinguishment of Unused Riparian Rights. Riparian rights are irreconcilable with prior appropriation because they do not require exercise to keep. How states handle this conflict varies: Colorado simply abolished previous riparian rights, while California adopted a statutory scheme that permitted riparian owners to keep their right, subject to certain restraints.

Constitutional Challenges: is extinguishing riparian rights a taking? Generally no, except in California, Nebraska, and Oklahoma. How other states have handled this in statute varies.

Administration of Hybrid Systems[edit | edit source]

Resolving Disputes Among Water Users. Like most of water law, it depends on the state.

Adjudication of Unused Riparian Rights. Some hybrid states (Texas included) have extinguished unused riparian rights, but created exceptions allowing riparians to claim water rights for future “domestic” purposes that are superior to all appropriative rights. Tex. Water Code § 11.303 (2013).

Prescription

Other Water Law Variations[edit | edit source]

Overview. Some water law systems are not easily characterized as prior appropriation, riparian, or as a hybrid of the two.

Water Law in Louisiana. Based almost entirely on the Napoleonic Code. Also worth noting that until recently, groundwater was almost entirely unregulated.

Hawaiian Water Law. In water’s natural state, it is part of the public trust. The Hawaii Supreme Court has also stated that Hawaiian rights are more akin to federally reserved water rights for Indian reservations than to true riparian rights.

Pueblo Water Rights. Has little recognition outside California, pertaining mainly to the rights of cities in California and of Indian tribes (pueblos) in New Mexico. Under pueblo law, actual use of the water is not required to keep a city’s right alive; a successor city may displace long-established uses even if it has not historically used the water.

Groundwater[edit | edit source]

Basic Hydrology[edit | edit source]

How Groundwater Occurs[edit | edit source]

Permeability of Rock Formations. Although permeability varies across a spectrum, rock formations are grouped into broad categories, described as “permeable” or “impermeable.” Whether water percolates through rock, and the speed at which it does so, are functions of the force of gravity and the permeability of the formation.

Percolation. Fancy way to say the water is just sitting there.

Interstices. The pores of the rock where water percolates. Formed by geological processes, or by later cracking or erosion. Varies based on the rock: gravel has interstices visible to the naked eye, while clay has minute interstices.

Porosity. The open space within a rock (think swiss cheese). Don’t confuse this with permeability! Measured by percentage of the rock’s volume occupied by pore space.

Molecular Attraction. Slows the movement of water through formations. Inversely proportional to the surface area of the rock particles (the smaller the rock, the higher the molecular attraction). For example, gravel is made of relatively large particles and has a low molecular attraction. Sand, on the other hand, has a much higher molecular attraction.

Permeability. Ability to transmit water. This considers porosity and molecular attraction.

Zones of Groundwater Occurrence. Almost all usable groundwater occurs within two miles of the earth’s surface and is commonly within a half mile. Groundwater is found in strata that may be defined as the zone of aeration and the zone of saturation, though other layers relevant to groundwater exist. From closest to furthest, they are:

Zone of Aeration. Moisture is present in the soil and accessible to the root systems of plants. Because it is held by molecular attraction, however, it cannot be captured readily by pumping.

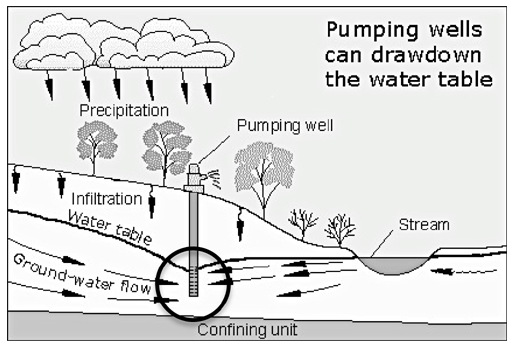

Piezometric Surface (Water Table). Also known as the water table.

Zone of Saturation. Underneath the piezometric surface is the zone of saturation, in which groundwater saturates the interstices completely. In this zone, water flows in response to gravity and can be withdrawn by pumping.

Bedrock. Impermeable; has a very low porosity.

Aquifers. permeable rock formations that yield water in significant quantities. Aquifers may be confined or unconfined, though most are unconfined.

Unconfined Aquifers. There is no upper layer that is impermeable. You have to pump these to get the water.

Confined Aquifers. Exist between two impermeable layers, and thus under more than typical atmospheric pressure.

Artesian Aquifer. A confined aquifer with an exit point below the water table. This causes the water to flow from the aquifer freely when tapped.

Perched Aquifers. An unconfined aquifer that sits above an impermeable stratum that is above another aquifer. These are often unaffected by withdrawals from the zone of saturation.

Spring. Any concentrated discharge of groundwater that appears on the surface as flowing water.

Rate of recharge. How quickly rainfall and other water returns to the aquifer. Some have such a low rate it’s functionally a non-recharging aquifer.

Safe Yield. The amount of water an aquifer can provide without being depleted.

Underground Streams Distinguished. Some water with a discernable boundary and flow can be considered an underground river. This is a factual question for courts to decide.

How Wells Work[edit | edit source]

Cone of Influence. As a well pumps, it warps the water table (see Figure 4). With enough withdrawal, this cone can deprive others of water.

Effects of Depletion. Depleting groundwater can affect the quality of the remaining groundwater, contaminate deposits, or cause subsidence.

Subsidence. When the land overlying an aquifer sinks. This is because the newly dry strata cannot support the weight above it without water.

Economic Consequences of Subsidence. Tends to be an economic externality (i.e. the cost of damage is not assessed to the individual pumper). But states internalize subsidence costs in their own way. Texas has imposed liability for negligent pumping, and confers power to control subsidence on groundwater conservation districts. Friendswood Dev. Co. v. Smith-Southwest Indus., Inc., 576 S.W.2d 21 (Tex. 1978); Tex. Water Code Ann. § 36.101.

Hydrostatic Pressure. The force that allowed permeated strata to support strata above it.

Optimum Yield. Groundwater suffers from the “Tragedy of the Commons,” where people are inclined to use as much as possible to claim it, rather than allow everyone reasonable access to preserve the good for long term.

Allocating Rights in Groundwater[edit | edit source]

Rights Based on Land Ownership[edit | edit source]

Absolute Ownership Doctrine: The Rule of Capture. Also known as the “English Rule.” Landowners have an unlimited right to draw any water found beneath their land. In some cases, this extends to even malicious pumping, though most states now have remedies for willful injury.

The American Rule. Similar to the English Rule, but only allows captured water to be used on the overlying land.

Correlative Rights. Similar to absolute ownership where you can pump underlying aquifers. However, you can only pump in relation to the amount of land you own above the aquifer.

Other Sources of Groundwater Rights[edit | edit source]

Rights by Prior Appropriation. The first in time has the best legal right. This can create issues, because in theory, a senior could claim no pumping because any amount would affect their usage. Appropriation states must determine the extent to which new uses will be allowed to interfere with established uses. Appropriators also may be limited in the uses they may make of groundwater in order to prevent an aquifer from being overused. Baker v. Ore-Ida Foods, Inc., 513 P.2d 627 (Idaho 1973).

Relation to surface water priority dates. Prior appropriation dates comingle between groundwater and surface water if they connect. Cause of action originates in one direction: so long as you have older surface water rights, you can put a call on younger groundwater rights. Hubbard v. Washington, 86 Wn. App. 119 (1997).

Groundwater as a Public Resource. Most states consider groundwater to be subject to management as public property. Police power is extensive enough to justify permit systems and strict regulatory schemes so long as vested property rights are respected.

Rules of Liability[edit | edit source]

Overview. Generally governed by theories of property law.

No Liability Rule. Followed in absolute ownership states (and some others as well). No obligation is incurred for harm or expenses caused to others. Sipriano v. Great Spring Waters of America, Inc., 1 S.W.3d 75 (Tex. 1999).

“Junior Pays” Rule. Found in prior appropriation groundwater jurisdictions. If a junior lowers the water table, they have to pay to improve the senior's equipment to reach the new water table. This may be subject to reasonable restrictions, depending on the state.

Reasonable Use Doctrine. The “American Rule” mentioned above. Some jurisdictions have also added correlative rights to the mix, finding that in cases of insufficient supply, each overlying user is entitled to a reasonable proportion. Higday v. Nickolaus, 469 S.W.2d 859 (Mo. Ct. App. 1971).

Restatement (Second) of Torts § 858. It imposes liability only for withdrawals that unreasonably affect other users. The Restatement approach differs from the American Rule by inquiring into the nature of the competing uses and the relative burdens imposed upon each user. It is distinct from the correlative rights approach in that it attaches no special significance to use of the water on overlying land. Spear T Ranch v. Knaub, 691 N.W.2d 116 (Neb. 2005).

Factors of § 858. A well owner is not liable for withdrawal of groundwater unless the withdrawal:

(a) unreasonably causes harm to a neighbor by lowering the water table or reducing artesian pressure; (b) exceeds the owner’s reasonable share of the total annual supply or total store of groundwater; or

(c) has a direct and substantial effect on a watercourse or lake and unreasonably causes harm to a person entitled to the use of its water.

What is unreasonable harm? First factor is a balancing test, taking into account value of use, relative financial capability of parties, and so on.

What is a reasonable share? The second limitation incorporates correlative rights as an additional basis of liability.

Considers connection to surface water. The last limitation contemplates administration of groundwater use in conjunction with surface appropriation systems.

“Economic Reach” Rule. The economic reach approach is somewhat similar to the Restatement in attempting to strike a balance between junior and senior rights. Specifically, seniors cannot be required to improve their extraction beyond what they can afford, upon a consideration of all the factors. Wayman v. Murray City Corp., 458 P.2d 861 (Utah 1969).

Permits[edit | edit source]

Overview. Most states require a permit to withdraw (save for small domestic wells). Texas doesn’t require a permit (except for Edwards Aquifer). There are two types of permits: well permits and permits evidencing a water right. The permitted rate of extraction is often a policy choice of the state. Permits can be abandoned, forfeited, or lost due to violating conditions.

Statutory Limits on Pumping[edit | edit source]

Overview. Limits on pumping depend on state policy choices, which tend to focus on the recharge rate of the aquifer, or other considerations of preserving extraction.

Protection of Existing Rights. Most statutory schemes seek to protect existing uses from unreasonable interference.

Prior Appropriation is not wholly compatible with non-recharging aquifers. In Mathers v. Texaco, Inc., 421 P.2d 771 (N.M. 1966), the court rejected the argument that any pumping whatsoever by juniors in a closed basin constitutes per se impairment just because pumping would lower the water table. However, according to the court, “it does not follow that the lowering of the water table may never in itself constitute an impairment of existing rights.”

Are these limits a taking? Actions by a city or other government body that destroy water quality or cause shortages for overlying landowners may also constitute a taking. McNamera v. Rittman, 838 N.E.2d 640 (Ohio 2005).

Texas approach to takings. Texas treats groundwater like oil and gas (rule of capture).

Conjunctive Use and Management[edit | edit source]

[Note: Eckstein has told us we will not be tested on this]

Overview. Joint use of hydrologically connected groundwater and surface water sources.

Regulation of Groundwater Connected with Surface Sources[edit | edit source]

Overview. Some states do not treat tributary groundwater as part of the surface system per se, but empower regulatory agencies to impose special conditions on groundwater withdrawals that interfere with surface rights. Officials have a duty to enforce those priorities. Musser v. Higginson, 871 P.2d 809 (Idaho 1994).

Some states are reluctant to tie ground and surface water together. Arizona (and some other states) require clear and convincing evidence that groundwater is part of the surface water regime. In re General Adjudication of All Rights to Use Water in the Gila River System and Source, 9 P.3d 1069 (Ariz. 2000).

When is there a cause of action from surface to groundwater? As always, it depends on the jurisdiction. In our case law, Hubbard and Spear T recognize a cause of action from surface against ground but favors surface users. Gila River does not recognize cause of action.

Definition of Hydrologically Connected (“Tributary”) Groundwater. The word “tributary” refers to groundwater that has a hydrologic connection with a surface stream that is sufficiently direct to warrant legal attention. Proving that groundwater is tributary to a stream can be difficult and expensive, but it has important legal consequences.

Gila River and the “Subflow” Theory. Ground water contained in the subflow is subject to the rules of surface water. Otherwise, groundwater law applies. This theory can allow surface rights to sue groundwater abusers.

How do you prove what’s subflow? The proponent must prove this fact by clear and convincing evidence.

Applying the Public Trust Doctrine to Interrelated Sources. Some states (Hawaii in particular) hold groundwater as part of the public trust as well. Other only apply public trust to groundwater connected to navigable surface water.

Groundwater Recharge and Storage. Slow to catch on, but case law supports three types of storage rights: (1) the right of a public agency to import and store water without obligation to overlying landowners; (2) the right to protect the stored water against use by others; and (3) the right to recapture the stored water.

Controlling Groundwater Contamination[edit | edit source]

Regulation of Groundwater Pumping[edit | edit source]

Overview. Because of the growing problem of contaminated groundwater, state permits are scrutinizing potential contamination more closely before giving permits.

Groundwater use not monitored, only extraction. Virtually no jurisdictions deny the right to use groundwater because the use, as opposed to the extraction, of water will cause contamination.

Regulation of Polluting Activities[edit | edit source]

State Regulation. Some laws classify aquifers according to the uses that can be made of them and allow more or less pollution to occur in order to protect those actual or anticipated uses. It is rare for the same agency that regulates groundwater allocation to regulate polluting activities. This often creates conflicts in regulatory power.

Federal Regulation. Many federal acts directly and indirectly affect groundwater pollution, but it doesn’t feel necessary to dive into each one. Includes the Clean Water, the Safe Drinking Water Act, the Solid Waste Act, the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA), the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA), and the Toxic Substances Control Act.

State Judicial Remedies. Most state courts entertain liability suits (nuisance, trespass, and negligence) by well owners against people whose activities cause groundwater pollution.

Pre-emption concerns. Groundwater contamination cases sometimes turn on whether federal statutes expressly or implicitly preempt state programs and actions. The outcome depends on a reading of the federal statutory provision to determine if Congress intended to preempt state laws.

Example: If Congress intended not to burden interstate commerce with varying state-by-state requirements, the state law may be preempted. On the other hand, if Congress intended to leave state remedial programs and causes of action intact as a way of making pollution control more effective, states laws are not preempted.

Diffused Surface Waters[edit | edit source]

[edit | edit source]

Federal and Indian Reserved Rights[edit | edit source]

Interstate and International Allocation[edit | edit source]

Interstate Adjudication[edit | edit source]

Applicable Law. How do we resolve state versus state cases when state laws are so varied? In an early case, the Supreme Court presumed that disputes among such users would be resolved by priority, as if no state boundary existed. Bean v. Morris, 221 U.S. 485 (1911).

Parens Patriae Suits. When one state sues private parties in another state in its role as parens patriae to prevent harm to its own citizens, the Supreme Court has original, but not exclusive, jurisdiction; there is concurrent federal district court jurisdiction. 28 U.S.C. § 1251(b)(3).

Limitations. Limited to major interstate rivers where there is a multiplicity of parties rather than litigation among individuals on a small stream with few competing users, as in Bean v. Morris, 221 U.S. 485 (1911).

The Doctrine of Equitable Apportionment[edit | edit source]

Background. Federal common law exists to handle water issues. In the rare instances where Congress has entered the realm of interstate water allocation, it has displaced the federal common law. Arizona v. California, 373 U.S. 546 (1963).

Overview. Announced in Kansas v. Colorado, 206 U.S. 46 (1907). A basic tenet of the doctrine is that “equality of right,” not equality of amounts apportioned, should govern. The Court is not bound by the laws of the individual states. The court may choose to apply what it feels is fair without strict application of one state’s law or another.

Relevant Facts. A state’s claim to divert waters for future use will turn on totality of the circumstances, including extent to which reasonable conservation measures by existing users can offset the reduction in supply due to diversion, and whether the benefits to the state seeking the diversion substantially outweighs the harm to existing uses in another state. Colorado v. New Mexico, 459 U.S. 176 (1982).

Objectives. Justice and equity; as well as efficiency and conservation.

Justice & Equity. Equitable apportionment calls for an informed judgement on the consideration of many factors (see below for factors).

Efficiency and Conservation. The doctrine imposes an affirmative duty for states to take reasonable steps to conserve and augment the water supply of an interstate stream.

Standards. Risk of diversion primarily should be on the party proposing the diversion. They must provide clear and convincing evidence, which will only be allowed only if actual inefficiencies in present uses or future benefits from other uses are highly probable.

Burden of Proof: Efficiency of Existing Uses. Requires specific evidence about how existing uses might be improved, or clear and convincing evidence that a project is far less efficient than most other projects. Mere assertions will not do.

Burden of Proof: Assessment of Future Benefits. A state proposing a diversion must conceive and implement some long-range planning and analysis of the diversion.

Factors. Application of the prior appropriation doctrine is qualified, however, in that the allocation must be equitable. Factors that inform equitable apportionment (and that might justify deviation from strict priority) include:

(1) Physical and climatic conditions;

(2) Consumptive use of water in the several sections of the river;

(3) Character and rate of return flows;

(4) Extent of established uses and economies built on them;

(5) Availability of storage water;

(6) Practical effect of wasteful uses on downstream areas; and

(7) Damage to upstream areas compared to the benefits to downstream areas if upstream uses are curtailed.

Another Approach: Mass Allocation[edit | edit source]

Mass Allocation Approach. The Supreme Court occasionally deviates from strict priority among appropriators in prior appropriation states by use of the “mass allocation” approach. See Wyoming v. Colorado, 259 U.S. 419 (1922), modified, 260 U.S. 1 (1922), vacated, 353 U.S. 953 (1957). Since the Court is reluctant to interject itself into intrastate allocations, it awards to each state a quantity of water to be distributed by the state’s appropriation system. The Court may hold that certain specific diversions are within one state’s share of the allocation, that a state may have a stated quantity of water, or that a state may have a given percentage of the flow, regardless of the mix of individual priorities within the state.

Interstate Compacts[edit | edit source]

Overview. Used to effectuate a variety of objectives by mutual agreement of two or more states. Compacts relating to interstate waters have been formed to allocate water between the states, but also to address issues involving storage, flood control, pollution control, and comprehensive basin planning (principally by joint federal-state compacts).

May allocate unappropriated water. Thus making a “present appropriation for future use.” The ability to make such determinations in advance is crucial to long range water planning.

Constitutional Authority. Typically, compact formation involves four steps. (1) Congress authorizes negotiation of the compact, usually providing for a federal representative at the negotiations. (2) The compact is negotiated and (3) the affected state legislatures approve the compact. (4) Congress must consent to the compact. When congressional consent is needed is debated, but the majority holds it is always required. State ex rel. Dyer v. Sims, 341 U.S. 22, 27 (1951).

Legal Effect of Compacts[edit | edit source]

Effect of Congressional Ratification. State legislation that conflicts with terms of an interstate compact cannot prevent enforcement of the compact. State ex rel. Dyer v. Sims, 341 U.S. 22 (1951).

Congress may override. Congress also retains power to override a compact provision by explicit legislation.

Unilateral state actions prohibited. These violate the Dormant Commerce Clause. Sporhase v. Nebraska ex rel. Douglas, 458 U.S. 941 (1982).

State compacts have the force of federal law. This may preempt inconsistent state laws. Hinderlider v. La Plata River & Cherry Creek Ditch Co., 304 U.S. 92 (1938).

Interpretation of Compacts. The Supreme Court is the final arbiter of the meaning of compacts.

Legislative Allocation[edit | edit source]

Overview. Congress has authority to act when the other apportionment mechanisms of compacts and judicial allocation have failed, are unavailable, or are not used. Arizona v. California, 373 U.S. 546 (1963)

Holdings from Arizona v. California. (1) Congress may, under its navigation and general welfare powers, apportion interstate streams by legislation. (2) Federal law controls both the interstate and intrastate distribution of project waters, preempting state water law. Therefore, the Secretary is empowered to allocate waters in times of shortage by any reasonable method, although “present perfected rights” must be satisfied.

Differences from Mass Allocation Doctrine. Note the contrast to the mass allocation approach, which leaves intrastate allocation to state law.

State Restrictions on Water Export. Water is an article of commerce. States may “conserve and preserve” water in times of shortage when measures are (1) reasonable, (2) not contrary to the conservation and use of groundwater, and (3) otherwise not detrimental to the public welfare. Sporhase v. Nebraska ex rel. Douglas, 458 U.S. 941 (1982).

International Allocations. Once the federal government enters into a treaty with another nation, it is the “Supreme Law of the Land” under the Constitution; any inconsistent state laws are preempted. Thus, treaties affect the manner and extent to which state-defined rights may be exercised.